Monthly Archives: April 2018

There is a line between dominance and abuse — and ‘Fifty Shades of Grey’ is blurring it

It’s a fairy tale to believe you can turn your abuser into someone who cares about consent.

After a year of incredibly romantic dates and the hottest sex ever, in my mid-20s, I awoke to find myself married to a man I loved who pushed me down the stairs of our house, held a loaded gun to my head, called me “retard” for kicks and strangled me while he climaxed.

I did not find being an abuse victim even remotely erotic. So it surprised me years later when a new boyfriend asked, while we were between the sheets, if the violence I suffered meant that I liked being dominated in bed, and presumably elsewhere.

With hype surrounding today’s release of the “Fifty Shades of Grey” movie, that question has moved out of my bedroom into our culture at large. If you are a woman who finds “Fifty Shades of Grey” erotic (as I did), perhaps you are interested in domination. But while sexual domination and abuse can sometimes look similar, they are very, very different. As a survivor of relationship violence, there is not one thing about real abuse that is sexy.

Nothing in my years of being manipulated, humiliated and psychologically broken by a man I once adored translated to sexual pleasure — or even an appetite for playing a submissive role. “The difference between playing a voluntary dominant or submissive role vs. being an abuse victim is simple,” explains Melissa Febos, a former dominatrix and author of the memoir “Whip Smart.” “It all boils down to consent.”

Erotic subservience requires mutual agreement and trust between partners. The “Fifty Shades” plot includes a contract between Christian Grey and Anastasia Steele, outlining the types of BDSM that are, and are not, acceptable to her. In abusive relationships, real trust is impossible; consent is never given, either implicitly or explicitly. Thus the pain is never voluntary, as it is in BDSM relationships. The idea that women find non-consensual abuse erotic is a myth reinforced by fantasy porn and by a widespread misunderstanding of relationship abuse.

There’s a hard line between fantasy and reality for most people. Pretending to appease a lover to heighten sexual pleasure is vastly different from silently submitting to your husband because he threatened to hurt your children if you refused him sex. Having a man’s fingers around my neck, squeezing so I could not scream for help or breathe, had a toxic impact on my libido — afterward I was never able to look at my husband’s hands as gentle or arousing. So when that beau asked whether I like to be dominated, my response was nothing more than laughter. How could anyone oversimplify the psychological complexity of relationship abuse? Why would anyone presume that victims of violence find violence erogenous?

Well, first off, many people wonder why women stay in abusive relationships; therefore, they might think we stay because we like it. Since we, as a society, don’t know what women actually do find erotic, this theory becomes somewhat plausible. Adding to the confusion is the disturbing truth that violent relationships are so common. On average, 24 people per minute are victims of rape, physical violence or stalking by an intimate partner in the United States — more than 12 million women and men a year. More than 60 percent of female homicide victims are killed by people they know.

The second, even more confusing truth that “Fifty Shades of Grey” highlights is the way some women harbor stubborn fantasies about their power to heal a damaged man. It’s not Christian Grey’s good looks, his garage full of Audis, or his personal helicopter that seduces Ana. It’s his raw emotional vulnerability that catches her attention initially. As their relationship deepens, his confessions of early physical and sexual abuse, along with an almost child-like willingness to open up his painful past to her and her alone, keep her hooked. The deeper, more dangerous fairy tale of “Fifty Shades of Grey” is that a strong, independent-minded woman such as Anastasia Steele can reach inside a troubled adult like Grey and heal the damaged boy inside.

Unfortunately, warped pity for a broken man can be potent and soul-crushing. It’s no coincidence that, after months of indecision, I decided to sleep with my future abuser the same night he confessed that his stepfather had starved and beaten him as a child. I remember a flood of passion intermingled with sympathy. I wanted to show that sweet boy what true love was all about and make him mine forever. His pain and his need to be healed turned me on emotionally – in ways that his need to control me never could sexually.

This emotional fantasy – not the sexual one – explains the 100 million copies the Fifty Shades franchise has sold and the buzz over the movie. For some victims, the intoxication of healing a damaged partner is the root of how love blindfolds us while delivering us into danger. We cling fiercely to the seductive idea that we are powerful, smart women who can fix hurt men; perhaps nobly, perhaps idiotically, we refuse to abandon these men when so many others already wisely have.

Neither the “Fifty Shades” books nor the movie ever get to the most vexing relationship conundrum: How do you find yourself again after losing your identity in a romantic relationship? And how do you avoid losing yourself in the first place? For survivors of psychological and physical exploitation, life after abuse is all about learning to trust yourself again. It took me years to let myself off the hook for marrying a man who, before we even got engaged, established limits for my skirt lengths and makeup application. To trust yourself that you’ll never get into an abusive relationship again, you need complete self-acceptance to admit you ignored the warning signs of abuse and voluntarily participated in the dance of repeat betrayal.

Consistent with its unusual mix of erotic and idiotic, the “Fifty Shades of Grey” trilogy ends with Ana and Christian’s happily-every-after marriage and vanilla sex – unlike real life, where most abusive relationships end with protective orders, blocked cellphone numbers, drawn-out court battles over children, or in the worst cases, death. The one thing the “Fifty Shades” plot has most in common with real-life abuse is its ability to present a psychological con as true love. Some viewers, like some abuse victims, have trouble discerning between delusional passion and reality. In order to end relationship violence, all of us – victims, perpetrators, parents, bystanders, lawmakers and moviemakers – have an obligation to destroy the myth that physical or psychological abuse ever plays a legitimate role in romantic or sexual realities.

More from PostEverything:

‘Social Surrogacy’ an Option for Moms-to-Be Who Shun Pregnancy

For most women, carrying their own baby is the ultimate joy, seen time and time again in movies, on TV and in magazines.

More and more women, however, are turning to surrogates to carry their babies, not because they cannot conceive, but because they do not want to.

It’s a trend many are calling “social surrogacy” and one that was recently highlighted in an article in the May issue of Elle magazine.

“This is a wonderful opportunity for women to have more choices,” said Dr. Saira Jhutty, CEO of Conceptual Options LLC, a California-based surrogacy agency.

Jhutty’s agency matches surrogates with women who have nonmedical reasons for not wanting to carry their own babies. The women who come to her agency have a variety of reasons for wanting a surrogate, from not wanting a pregnancy to interfere with their careers to being afraid of what pregnancy will do to their bodies, Jhutty said.

“We have people who are afraid of being pregnant,” Jhutty said. “Some people work in an industry where image is very important so they don’t want to have to go through the changes that happen to a woman’s body when they get pregnant.”

But the choice is still a touchy subject, despite the rising interest in “social surrogacy.”

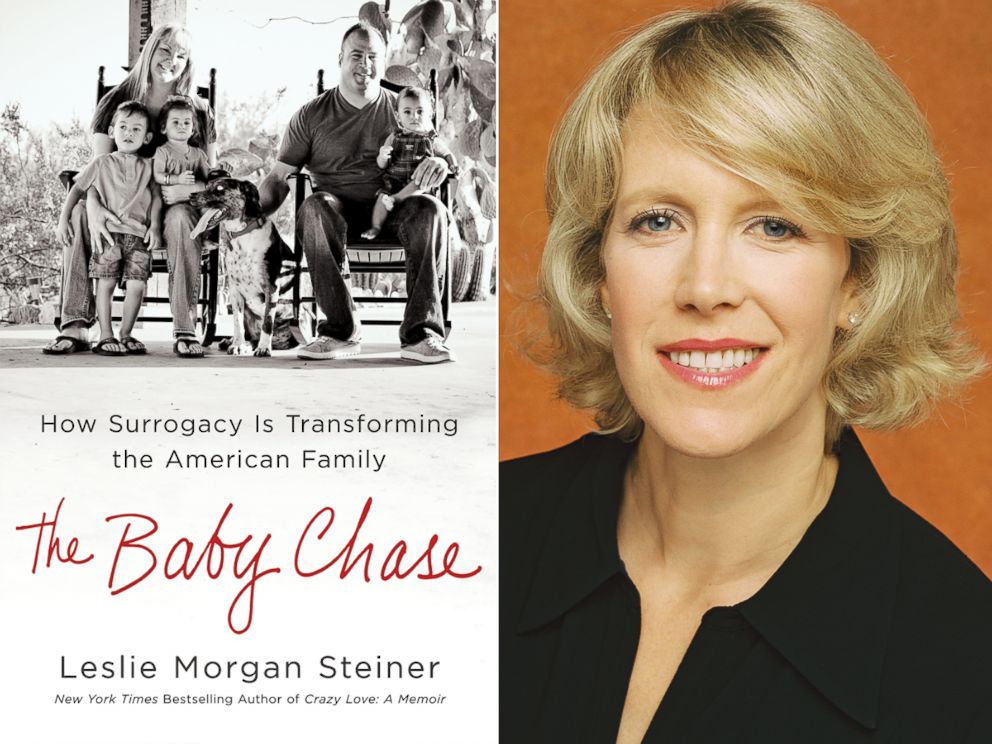

“Women are really guarded about issues involving their bodies and surrogacy because they are afraid of being judged,” said Leslie Steiner, author of “The Baby Chase: How Surrogacy Is Transforming the American Family.”

The cost is another issue that might give women pause. With surrogacy running $100,000 or more per child, it’s not for everyone.

“You have to ask yourself why you are doing this,” said Dr. Vicken Sahakian, medical director of the Pacific Fertility Center in Los Angeles. “Is there real benefit for bypassing the beautiful experience of carrying a child?”

Motherlode Must-Read: ‘The Baby Chase: How Surrogacy Is Transforming the American Family’

“The Baby Chase: How Surrogacy Is Transforming the American Family,” by Leslie Morgan Steiner, was among the best books on family from 2013. I’ve been meaning to share it with you for some time, and Amy Klein’s post about donor eggs (“Would a Pregnancy Through a Donor Egg Feel Like ‘Mine’?”) and the resulting discussion of the medicine and ethics of egg donation, and in particular overseas egg donation, provided a perfect opportunity. If you’re at all curious about egg donation and surrogacy (in fact, if you’re just a curious reader at all), “The Baby Chase” makes a fascinating read.

The author takes a Tracy Kidder approach, using a strong voice and a personal narrative to frame the larger story of the history of surrogacy (which incorporates the history of donor eggs) and its place in fertility medicine today. It’s not her story she tells, but that of Rhonda and Gerry Wile, and of the Indian doctors and surrogate who ultimately (after an agonizing journey through every failure imaginable) help them to create their family of three children.

As a fan of memoirs, I appreciate the weaving of fact into a narrative, but “The Baby Chase” works better without the autobiographical burden. That the writer isn’t her own subject here gives her enough distance to offer the reader a picture of surrogacy as a whole, rather than as a solution. This is a book about parenthood, fertility and biology, but not necessarily in that order.

Every question is covered: the mechanics of surrogacy, the choice of a donor egg, the process and medical issues surrounding egg donation, the selection of a surrogate — and, of course, the ethics of it all. By telling the stories of both the surrogates who ultimately carry the children and the doctors who’ve created the clinic where the Wiles ultimately find success, as well as the story of the Wiles themselves, Ms. Steiner gives the reader a chance to hear the positive assertions of the benefits of surrogacy to the surrogates — and to draw her own conclusions based on the lived experiences of the women, which aren’t entirely positive or entirely negative. “The Baby Chase” delivers on the promise of the best journalistic nonfiction. It’s a captivating glimpse into a world and a journey most of us will never experience.

Who Becomes a Surrogate?

There are often “have” and “have not” differentials at play in the surrogate-intended parent relationship. The surrogates already have the ability to create babies; the intended parents have money. They are usually better educated, and far more economically secure. Sometimes these dynamics can create subtle tensions.

On a blue-sky afternoon in early November, a few days after Halloween, yellow leaves and a few Reese’s candy wrappers littered the cobblestone sidewalks ringing the Maryland State House. The circa-1772 redbrick, white column Annapolis landmark is the oldest American edifice still in legislative use. Our infertile founding father, George Washington, resigned his military commission here in 1783. Three years later, patriots rallied in the State House to call the thirteen American colonies to assemble for the Constitutional Convention. Another 225 years later, red, white, and blue American flags, as well as Maryland’s black, gold and red ones, fluttered at every window.

On the third floor of a small, anonymous office building directly across the street, Sherrie Smith sits behind her desk. She works only a few blocks from the Annapolis wharf, with its rustic “shoppes,” historic landmark buildings, pretty white sailboats and blue-glass water. Close-shaven cadets in black uniforms walk to town from the nearby United States Naval Academy.

“Having a baby for someone else is as far from easy money as you can get.“

Sherrie is always too busy to see much of the historic scenery outside her office. She’s buried in her email queue, conducting interviews via Skype and answering the phone. Her job is educating, listening to, and holding the hands of anxious, usually very wealthy, prospective parents from around the globe. She is the program administrator for the Center for Surrogate Parenting, one of the oldest, most respected surrogacy agencies in the world.

“The biggest misconception about American surrogates?” she clarifies in the beige-on-beige CSP conference room where she spends much of her days. “That they do it for the money. Having a baby for someone else is as far from easy money as you can get.”

Sherrie Smith has run the East Coast office of the Center for Surrogate Parenting since 1998. She’s now in her 60s. Although she chose not to have kids of her own, she and CSP have helped nearly 1,700 surrogate babies come into this world. CSP’s most famous babies include two sets of twins for Good Morning Americahost Joan Lunden, and Zachary Jackson Levon Furnish-John, the baby boy born on Christmas Day 2010 for pop rocker Elton John and his husband David Furnish.

Sherrie’s company was founded in Los Angeles, California in 1980. Sherrie’s boss—a Los Angeles lawyer by the name of William Wolf Handel—wrote a third party reproduction agreement, now called a “surrogacy contract,” as a random, one-off request for a client. Word quickly spread among infertile clients desperate to hire surrogates to have babies. The phone at Handel’s Los Angeles law office started ringing off the hook.

Bill Handel and his staff—all women except the boss—at first struggled to craft a workable set of guidelines in the brave new world of contractual baby making. They knew they’d stumbled upon a promising business opportunity—but a risky one. What if the surrogate changed her mind? Many desperate prospective parents asked. A reasonable question, without a clear-cut answer; no legal precedents had been established. So Bill Handel’s female-centric firm came up with an innovative business philosophy: the surrogate herself would have equal standing among the team of doctors, wealthy clients, and lawyers. With a democratic approach, Handel figured that they had a good chance of solving any problems that arose.

“It was impossible to write a contract—or create a company—that was unfair to women when all my employees and partners were women,” Handel explains today. Other women in Handel’s life added their two cents. In addition to his estrogen-rich office, the female clients who hire him, and the surrogates his company hires, insert one wife and two daughters. Women surround Bill Handel 24 hours a day.

“I live in a world where the toilet seat is never left up,” Handel clarifies, laughing.

Lucky for him, the approach proved wildly successful. Almost by accident, the Jewish, Brazilian-born Bill Handel became a pioneer in California surrogacy law. Over the years, his advocacy—plus a plethora of wealthy, high-profile celebrities who publicly embraced surrogacy—helped make California arguably the most surrogacy-friendly environment in the U.S. It also made CSP one of the finest, and most expensive, providers of surrogates in the world.

The first surrogate Sherrie Smith encountered had been hired by someone she loved so much, Sherrie would have supported her adoption of a Pet Rock: her sister Fay Johnson. After years of negative pregnancy tests and myriad infertility diagnoses, Fay Johnson became one of the earliest American women to go public about hiring a paid surrogate. Sherrie’s niece and nephew were both born via surrogate in California, in 1990 and then 1994.

During the years since, Sherrie has learned a great deal about the American surrogates who carry babies for infertile clients from around the world.

The clients are usually older, richer, better educated, often with graduate degrees, and more likely to come from large urban cities like New York, Los Angeles, Paris, and Tokyo. CSP’s clients are far better traveled than the surrogate mothers they hire. Intended parents (IPs) come from Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Bermuda, Canada, China, Columbia, Cyprus … Denmark, Egypt, England, France, Germany, Hong Kong, India, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Indonesia … Japan, Kazakhstan, Korea, Lebanon, Luxembourg, Malaysia, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, Papua New Guinea … New Zealand, Peru, the Philippines, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Scotland, Singapore, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Turkey and Venezuela.

The majority of intended parents are heterosexual couples. Some are infertile due to biological abnormalities. Others face fertility challenges wrought by hysterectomies, car accidents, paralysis, or other medical problems. More and more are gay male couples (lesbian couples rarely hire surrogates, given the inexpensive, thoroughly-screened sperm on the market and the statistical improbability of two female partners both being infertile). Increasingly, there are more single women and single men who are consciously and openly choosing to become solo parents. CSP originally worked only with couples, but in 2009 the company changed its guidelines to welcome single parents.

Surrogates already have what the IPs desperately want—the ability to create babies. What the IPs have is money.

The surrogates are obviously all female, and they’re noticeably younger—the average age is about 28. The typical profile runs like this: married, Christian, middle class, with two to three biological children, working a part-time job, living in a small town or suburb rather than a big city, with a degree of college education but usually without a college degree. Women who shop at Wal-Mart and Costco, not Whole Foods and Neiman-Marcus.

In the United States, statistics show that surrogates fall into the average household income category of under $60,000. About 15 to 20 percent are military wives. Some are single women. Those who are married have husbands who support paid surrogacy; surrogacy is obviously not something you can hide, or withstand with a spouse who is not on board emotionally. They have health insurance. They get paid well—the surrogacy fee paid directly to surrogate mothers who work for CSP runs from $20,000 to $30,000 per pregnancy, tax-free. Experienced surrogates often command higher fees; as in any position, experience counts. Of the women who serve as surrogates for CSP, roughly 35 percent repeat the experience; in the U.S. there is no limit to the number of times a surrogate can carry for-profit babies.

CSP is not alone in its strict criterion for surrogates. Ethical surrogacy agencies and lawyers don’t accept two specific categories of potential surrogates. First, they reject women below the poverty level who may be at greater risk for health concerns and coercion, and who probably do not have medical insurance. Second, they reject women who don’t have children. Women who are already mothers have proven they are fertile, and have a more comprehensive grasp of what it will mean to surrender a baby to its legal parents.

Although the money makes a difference, no surrogate signs up just for the money.

“It would be easier to get a job at McDonald’s,” Sherrie insists. “The money doesn’t begin to compensate them for what they do. A surrogate pregnancy means working 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, without a break, for nine months. Pregnancy is risky; pregnancy taxes your body tremendously. Our surrogates come to us because they love children, they want to help people who cannot have them, and they like the feeling of creating a family for other people.”

Yet undeniably, you’ve got “have” and “have not” differentials at play in the surrogate-intended parent relationship. The surrogates already have what the IPs desperately want—the ability to create babies. What the IPs have is money; they are usually better educated, and far more economically secure. They must be, in order to afford the surrogate’s fee, the agency fee, legal fees, and surrogacy’s medical expenses.

The IPs are consumed by desperation. As a result, their surrogate becomes, at least for nine months, the superwoman in their lives, the embodiment of their most fervent hopes and dreams. Working at McDonald’s or temping as a law firm receptionist can’t compare to being a wealthy, educated couple’s savior. Sometimes these economic and fertility dynamics can create subtle tensions; many times the enthusiasm of the surrogate and the gratitude of the intended parents smooth over any jagged feelings.

Surrogates do not pay taxes on the payments from clients, which technically are for pain and suffering incurred, not for carrying a baby.

Some quirks about surrogates. There are very few Jewish surrogates—and almost zero Jewish egg donors. Black surrogates carry babies for white families and vice versa. Surrogates do not pay taxes on the payments from clients, which technically are for pain and suffering incurred, not for carrying a baby. Daughters of surrogates frequently decide to be surrogates themselves; surrogacy can become a family tradition. Gay men are the favorite clients of many surrogate moms; one emotional complication is removed from the tricky relationship, because the gay intended parents don’t suffer the understandable jealousy/inferiority issues that can plague infertile intended mothers.

CSP selects only twenty of the 400 women who apply each month to be surrogates. The most common reasons for rejection? The surrogate lives in a state where commercial surrogacy is not legal. She has health issues such as high blood pressure or obesity. Her motivation is too heavily focused on money. She lives too far away from a level two NICU. She has not yet had a child.

What takes up most of Sherrie’s time is interviewing and managing the clients who retain CSP to oversee the complex surrogacy process. Step one is completion of an online form, available from CSP’s website, followed by a phone call with Sherrie. Step two is a half-day interview, conducted in person in Sherrie’s conference room or via Skype (particularly useful for international clients, who account for close to 50 percent of CSP’s parents). The interview includes a 45-minute preliminary psychological consultation with one of the independent counselors who work with CSP. Then clients must meet with an attorney familiar with state-by-state surrogacy laws and contracts, as well as international citizenship regulations if the client is from another country.

The first phase in surrogacy has nothing to do with babies, and everything to do with meetings.

During these lengthy consultations, everything about the process—the risks, unknowns, legal paradoxes, and costs—are laid out. Sherrie is a skilled communicator; the most important part of her job is talking and listening. She goes through the minutiae of health insurance clauses that exclude coverage for surrogate pregnancies. She diplomatically broaches whether a surrogate or a client would be amenable to reducing a multiple pregnancy, or terminating a pregnancy if the fetus has birth defects, both important issues to clear up long before they become realities, especially because forcing a surrogate to have an abortion is legally, and ethically, problematic.

Sherrie Smith wants to see glassy eyes on her prospective clients’ faces.

“The only surprise we want clients to have,” Sherrie makes clear. ”Is whether they’re having a boy or a girl.”

Infertile Americans Go to India for Gestational Surrogates

Rhonda and Gerry Wile of Mesa, Ariz., struggled with infertility for years. At first, Rhonda failed to get pregnant because her husband had not told her about a vasectomy he’d had in his first marriage. The news, received by an email in 2004 when he was serving in the Coast Guard in Kuwait, nearly derailed their four-year marriage.

Gerry had his vasectomy successfully reversed, but after suffering a miscarriage, Rhonda was diagnosed with uterus didelphys, a not too uncommon condition with a septum or dividing wall between two vaginas that leads to a double uterus. They said she likely could not sustain a pregnancy full-term.

So the couple turned to gestational surrogacy, a growing trend among American women for whom in vitro fertilization is not an option. They didn’t stay in the United States, but went abroad to India, where surrogacy is now one of the fastest-growing segments of the medical tourism business.

Having two vaginas is not so rare.

“When doctors told us surrogacy was one of the options for us and then a young lady at work told me the price, I felt we had hit a roadblock again,” Rhonda, a 43-year-old nurse, told ABCNews.com.

But today, the Wiles have three children, a 4-year-old boy Blaze, and 2-year-old girl/boy twins, Dylan and Jett. Gerry, a 47-year-old firefighter, made one sperm donation in April 2008, and their children were conceived though a Muslim Indian egg donor the couple had never met. All three are full biological siblings.

“We knew it was huge to go to India,” said Rhonda. “We could show up and it could be a phony website and we could be taken for a ride. But as we got more familiar and deeper into the process, our fears faded away. We met the doctors and spent time with them and there was an immediate connection and sense of trust.”

Their unusual but touching journey is the subject of Leslie Morgan Steiner’s new book, “The Baby Chase: How Surrogacy Is Transforming the American Family.”

“I wanted to look at what happens when we can’t have children and the lengths we go to,” said Steiner, author of “The Mommy Wars” and “Crazy Love.” “How far would I go to have a baby? As I got into it and learned more about it, I realized there were complex medical, ethical and religious issues. It was so multi-faceted.”

“Infertility is a cruel and crippling disease, and surrogacy is one of the solutions — for some, it is the only solution. — Leslie Morgan Steiner”

Steiner followed the Wiles to India to investigate the private clinic where their children were conceived and to meet the gestational carrier of their twins.

The cost for all three children was about $50,000 compared to an estimated $100,000 a child in the United States. And the Indian women who carried the pregnancies, who typically earn about $60 a month, each received the equivalent of $6,000.

Indiana couple braces for second set of triplets.

What India has to offer, according to Steiner, is “world-class private hospitals, an abundance of English-speaking doctors, and a plethora of poor, but healthy women of childbearing ages.”

No data yet exists on how many surrogate births take place in India, but Steiner contends India has become the largest provider to infertile couples in the Western world outside the United States.

These are reputable clinics, according to Steiner. “They only want mentally and physically healthy surrogates who have already had children and have proven their fertility and can gestate a baby and women who understand the complexity of what they are doing.”

“When you have a baby 8,000 miles away, you need a lot of reassurances that the surrogate is going to get good medical care,” she said. “They sign a contract not to have sex, to take vitamins and eat healthily. The clinic goes the extra mile to cook and take care of them and they see the doctor in a regular basis.”

Legal since 2002, gestational surrogacy is thriving in more than 1,000 clinics in India. According to a World Bank report, the commercial surrogacy industry in that country will reach $2.5 billion by 2020.

A bill is before the Indian Parliament that will for the first time regulate this nascent industry, but critics say that its provisions lack adequate protections for the women who act as surrogates.

But Steiner argues it is “empowering” for these women. “India is a very sexist and paternalistic country. The vast majority of women never work their entire lives. … But a woman can buy a house or pay for the lifetime education of her children. Going in as a Westerner, you think these women are being taken advantage or exploited, but it’s exactly the opposite. They become heroes in their families and among their neighbors.”

Dr. Sudhir Ajja, co-founder of Surrogacy India, the Mumbai clinic where the Wiles’ children were conceived and delivered, said about 95 percent of his clients are international — 30 to 40 percent Americans, followed by Australians and Swedes. His clinic, founded in 2007, delivers about 302 babies a year, averaging 15 to 20 new pregnancies a month.

He and his co-founder had seen clinics doing surrogacy on an out-patient basis and said they wanted a more “humane” approach with more medical oversight.

Surrogate mothers are put through a rigorous screening process for physical and psychological health, and the clinic rejects more than a third of them.

At first, surrogacy was considered shameful by Indian women.

“Things have changed,” Ajja told ABCNews.com. “We have thousands [of women offering to be surrogates]. We now get referrals from sisters, sisters-in-law and word of mouth.”

The surrogates receive free medical care, food and even housing close to the clinic, where they can be monitored by medical professionals in the third trimester. The fee paid by couples includes the surrogacy fees, IVF, medical testing, legal documents and passport assistance.

Author Steiner doesn’t suggest there are no potential problems with international surrogacy. “It’s not a perfect world,” she said. “India has a big problem with forced prostitution and there is a high incidence of female infanticide. So it is a bit ironic that surrogacy is flourishing.”

Rhonda learned about the Indian clinic on an “Oprah” show and then by searching the Internet. When they saw the cost, about $26,000, she said, “I thought it was do-able.”

The only references the couple had was a man from Spain, “who spoke very broken English,” said Rhonda. But when they arrived in India and saw the birthing hospital and the accommodations for the surrogates, “we felt good about the process,” said Rhonda. “It was very professional.”

Through both pregnancies, the Wiles kept in touch with the surrogates via a language interpreter on Skype. When Blaze was about 18 weeks in utero, the couple decided to go to India and meet his surrogate.

“We wanted to see the ultrasound and we set up a meeting and made the trip to go halfway around the world,” said Rhonda. “It was fabulous.”

What she learned was that the woman was the mother of two boys, married to a factory worker. “She did basically what 90 percent of the surrogates do – she wanted to buy a house as her goal.”

As for the twins, their surrogate “was poverty-stricken,” said Rhonda. “She needed money to survive and was having a hard time making ends meet. Her husband was out of work quite often and she needed to put food on the table.”

Now, on her blog, Our Journey to Surrogacy In India, Rhonda recommends her experience to other infertile American couples.

“We became a reference for others,” she said. “It’s amazing. People have sent me messages and still thank me for their children: ‘Without you, we would not have a child.'”

As for Steiner’s book, Rhonda said, “I loved it. I read through the entire book and took time to read it quietly and in detail to bring it all in. I literally relived my whole journey through her eyes. I cried. I laughed. I lived it through her.”

‘The Baby Chase’ by Leslie Morgan Steiner

“Surrogacy is as old as the Bible,” one American surrogate mother tells her critical mother-in-law. “We’re just helping other people have babies. It’s a beautiful thing.”

Leslie Morgan Steiner seems mostly to agree. In her new book, “The Baby Chase,” Steiner tackles some of the legal, ethical, religious, and social thickets that arise when people use advanced reproductive technology, including the uterus of a stranger, to make a baby for themselves.

But while offering some acknowledgment to the controversies surrounding surrogacy, the author comes down firmly on the side of prospective parents who’ve found themselves out of medical options and stymied by adoption red tape. For them, “infertility can become an insurmountable, intensely personal, crushing” burden, one intensified by religious condemnation, social ignorance, and financial strain.

An Open Letter to Rihanna

Dear Rihanna,

As I write this, the tabloids and TV news channels are obsessing about your relationship with Chris Brown. They want to know why you two reconciled, how many attacks you may have hidden before the one that made headlines in February, and what you’ll do if he’s tried and goes to jail. Reporters go on and on about battered women and their maddening tendency to forgive the men who hurt them, not realizing their words blame the victim. I know how that must feel. They could be talking about me.

When I was in my early twenties, I fell in love with a “perfect on paper” guy (Ivy League degree, big Wall Street job) who beat me and degraded me in ways I never could have imagined. I did not leave him the first time. Or the second time. It wasn’t until four years after our wedding day that I finally staggered out of our marriage as unrecognizable to myself as you must have found your own bruised, swollen face to be. So I’m not going to tell you or anyone else to leave someone you love and expect that will solve all of your problems. I know from experience that leaving is easy. The tough part is figuring out how to pick up the pieces of yourself and make a new life.

I was 22 when I met my abusive lover. I’d just graduated from Harvard and had landed a great job at Seventeen magazine in New York. He was funny, self-deprecating and scrappy in a way I adored. One night he told me that he’d been abused as a child. I listened and I loved him, confident that I could be the one to help. A few of my friends tried to warn me off dating a man with a temper and a rocky past, but I didn’t listen. I thought I could handle it.

Then, on our island honeymoon, he attacked me twice while I was driving the rental car. I had gotten lost looking for a barn where we were supposed to ride horses; his reaction was to punch me so viciously that my head hit the side window. A few days later he threw the cold remains of a Big Mac at me while I drove on the highway. At first I excused each attack. He was stressed, I told myself. But eventually the abuse became routine. He pushed me down the stairs, poured coffee grounds on my head and once pulled the keys out of the ignition as I went careening down the highway at 55 miles per hour.

All the while, I kept his assaults a secret. It never occurred to me that someone outside our relationship would understand; I was sure they would blame me for provoking him or think I’d blurred the line between a heated argument and abuse. I did not know then that The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that 2 million women are injured by their husbands or boyfriends each year. Three of those women die every day.

It wasn’t until my ex-husband almost killed me that I realized we weren’t just an ordinary couple with some problems. Six months earlier I’d given him an ultimatum that if he hit me again, I’d leave. To celebrate such a long happy stretch—and our anniversary—we planned a trip to Paris. The night before we left, he attacked me. It was as if he’d been saving up six months’ worth of anger; his beating was that brutal. My denial broke; for the first time I was scared, terrified actually. Neighbors heard and intervened. The police came. And I left my marriage.

I made a list of all of the people I had to tell. At the top was my mother. I was so scared to disappoint her, but her response was to give me a gift: a gold ring in the shape of a butterfly. I couldn’t think of what I had to celebrate, but I got her point immediately: cocoon, butterfly, new life. I knew I was being transformed into something more beautiful in her eyes. And each time I went to the police station or to court to file another restraining order, my mother’s present reminded me that while I may have felt like damaged goods, I wasn’t.

I left my marriage broke and broken—physically, emotionally, financially and socially. It took me years to pay off our debts, to enter a room with an easy, confident smile, to fall in love again and trust that the man I loved would not raise a finger to me, ever. But I did. My message to any woman who’s been betrayed is this: You have another life waiting for you. You may be isolated, but you’re not alone. I hope to welcome you into a very exclusive girls’ club. One filled with wise, wise women whose experience with abusive love rests deep in the past.

Looking at my life now—my quiet, kind husband, our three kids, a satisfying career, a beautiful home—you’d never guess that I spent my twenties hiding cuts, bruises and a broken heart. At 22, before the beatings started, I thought I was merely lucky—lucky to have my degree, my job, my cute apartment, my boyfriend. But I don’t place my faith in luck anymore. Some of us take our lessons in love straight up. Everything I have now I earned with hard work and hard lessons, plus a stubborn faith that I deserved, despite everything, to live happily ever after. We all do.

With love and support,

Leslie Morgan Steiner

Author of the new book Crazy Love, a memoir of her abusive relationship

Teens Closely Watching Chris Brown, Rihanna

The alleged domestic violence incident involving R&B stars Chris Brown and Rihanna has stirred serious discussions about abusive relationships among teens.

Leslie Morgan Steiner is author of Crazy Love, which details Steiner’s abusive first marriage. Steiner is joined by regular parenting contributors Dannette Tucker, who also survived an abusive relationship, and journalist Asra Nomani to explore ways to discuss abuse with youngsters who claim to be in love, and why many victims suffer in silence.

Nomani also explains the case of Aasiya Hassan, a New York woman who was recently beheaded. Hassan was allegedly murdered by her husband, Muslim media tycoon Muzzammil Hassan.

Excerpt: ‘Crazy Love’

NOTE: THIS EXCERPT CONTAINS LANGUAGE THAT MAY BE OFFENSIVE TO SOME AUDIENCES.

Chapter 1

If you and I met at one of our children’s birthday parties, in the hallway at work, or at a neighbor’s barbecue, you’d never guess my secret: that as a young woman I fell in love with and married a man who beat me regularly and nearly killed me.

I don’t look the part. I have an MBA and an undergraduate degree from Ivy League schools. I live in a red brick house on a tree-lined street in one of the prettiest neighborhoods in Washington, DC. I’ve got 20 years of marketing experience at Fortune 500 companies and a best-selling book about motherhood to my name. A smart, loyal husband with a sexy gap in his front teeth, a softie who puts out food for the stray cats in our alley. Three rambunctious, well-loved children. A dog and three cats of our own. Everyone in my family is blonde (the people, at least).

Ah, if only being well-educated and blonde and coming from a good family were enough to defang all life’s demons.

If I were brave enough the first time I met you, I’d try to share what torture it is to fall in love with a good man who cannot leave a violent past behind. I’d tell you why I stayed for years, and how I finally confronted someone whose love I valued almost more than my own life. Then maybe the next time you came across a woman in an abusive relationship, instead of asking why anyone stays with a man who beats her, you’d have the empathy and courage to help her on her way.

We all have secrets we don’t reveal the first time we cross paths with others. This is mine.

I met Conor on the New York City subway, heading downtown, 20 years ago. I was 22. I remember it like yesterday.

The window in Kathy’s office was the only daylight I could see from my presswood desk in the hallway. I snuck a look. My ugly orange swivel chair squeaked.

It was a chilly, gray Monday afternoon in mid-January. The midtown Manhattan skyscrapers were slick and dark with rain.

First thing that morning, Kathy — head of the Articles Department at Seventeen and the first boss I’d had in my life — held a meeting to dole out assignments for May. Then I interviewed a fidgety twelve-year-old Russian model who looked 29 with makeup on. After that I ran out in the rain for lunch with the wacky British astrologer who wrote Seventeen’s monthly horoscope column.

I’d graduated from college the spring before on a day when Harvard Yard looked like the opening scene from a big-budget movie. Sun-dappled spring grass. My mom happy-drunk in a striped Vittadini wrap dress. My dad so proud I thought his face would split open, beaming as only a poor Oklahoma boy with a daughter graduating from Harvard could.

The day so lovely I wanted to hold it forever in my hands.

Working at Seventeen was better than a Baskin Robbins sundae. We read magazines all morning and talked about sticky teenaged paradigms on the clock. In the afternoons we raided the Fashion Closet– a huge room where the Fashion editor kept designer samples that transformed gawky teenage ostriches into goddesses. I hated the few times I’d gotten sick and had to miss a day.

Outside Seventeen I roamed New York City like my new backyard. Dinners at the Yaffa Café and Bombay Kitchen. Hours dancing with my roommate at Danceteria or Limelight. Even the most mundane activities — folding clothes at the fluorescent-lit Laundromat across 8th Avenue, jogging through the Meat Packing district — became adventures.

But it was tricky getting the whole work thing down. Putting on pantyhose like a uniform, no runs my frantic morning mantra. Getting on the E train instead of the express to Harlem. Figuring out how to eat when my paycheck ran out six days before the next one was due.

Everything seemed so new.

I wrote and rewrote that afternoon at my desk in the hallway as the rain poured down outside Kathy’s window. Every girl in America read Seventeen’s at some age. Nearly four million girls devoured each issue; some favorites became like bibles for girls who had only a magazine to turn to for advice.

I should know.

Every day, often with little support or guidance, a teenage girl tackled staggering dilemmas. If your boyfriend offered drugs, did you do them? Did buying birth control make you a slut? Where did you get birth control at 16, anyway? What if your best friend drove drunk with you riding shotgun? Your stepfather came on to you? Your parents got divorced? Your mom got cancer?

My piece was slated for March, meaning I had to finish it by…Friday.

“Almost done?” Kathy barked as she whizzed by in her black patent leather boots with three-inch heels. I jumped off my chair.

The story itself asked a simple enough question: why do teenagers run away from home? But after pouring over government statistics and interviewing social workers, psychiatrists and the four runaways who would actually talk to me, I’d come to an awful understanding.

Of the estimated 1.5 million teenagers who hit the streets each year, the majority bolted because they thought any situation would be better than home.

Twenty-five percent came from families with alcohol or drug abuse.

Fifty percent had been sexually or physically abused by someone in their household.

What kind of home was that?

The realization that broke my heart: all runaways start out fighting for a better life. The survival instinct that gave them courage to leave bad homes made them try to turn the streets into a new home, the other runaways their families.

Within months, two-thirds were using drugs and supporting themselves through prostitution. Close to a third didn’t know where they’d sleep each night. One-half tried to commit suicide. Two-thirds ended up in jail or dead from illness, drug overdoses, or beatings by pimps, johns or other homeless people.

When I finally looked up from the computer I was the only one left at the office, feeling like I’d been ditched by the cool girls after school in eighth grade. My watch read six p.m. It seemed like midnight as I trudged to the subway in the rain.

Winnie took forever to unlock the three deadbolts on her apartment door.

We hugged; she was only 5’2″ so the top of her head butted against my chin. As always, her hair smelled like honeysuckle.

I dropped my purse in the foyer and started unlacing my L.L. Bean duck boots, indispensable during the snowy Cambridge winters and slushy springs. Ridiculous footwear now that I lived in the fashion capital of the planet.

“How was work?” she asked. Winnie (short for Winthrop – I’m not kidding) was wearing a white cotton shirt with a high ruffled collar, threaded with a pale cream sliver of silk, tucked into a long brown suede skirt.

“Great … I’m writing about teen runaways.”

I shook the wet boots off my stocking feet. I had a harder time shaking off the images of the 14-year-old girl I’d interviewed for my story. The one who slept on a subway grate and blew her hair dry in a corner of the Trailways bus terminal next to the pay phone she refused to pick up to call home.

“So how was your work, Win?”

She was a salesgirl at the Polo Mansion at 72nd and Madison selling outrageously priced Ralph Lauren clothes to celebrities. She had to wear all Ralph Lauren clothes. Blonde Wasp perfection every day.

“Oh God, it’s a long day when you’re on your feet trying to smile at all those rich assholes.”

Something on the stove started hissing like an angry cat.

“Fuck!” she yelled. Even in fourth grade, she swore like a 35-year-old divorcee. I followed her into the tiny kitchen.

She took the pot off the burner and turned back, smiling. Even Winnie’s teeth were cute. That was one of the first things I noticed the day she showed up at elementary school. Over the next three years she taught me the following life essentials: how to shave my legs with Spring Green Vitabath, sleep until noon, and look up sex words in the dictionary. I loved wearing her preppy clothes, smelling like Winnie’s laundry detergent even if just for a day.

The year I turned 13 I grew four inches, began smoking pot, drinking tequila and dating older guys. I totally outgrew Winnie’s entire closet. Her Lacoste shirts wouldn’t cover my belly button anymore.

When I drank, she was one of my favorite people to call late at night. “I love you Winnie,” I would slur into the phone. She was always pretty nice about those calls.

“Look!” She held out her left hand, fingers splayed, so I could get a full view of her sparkly new engagement ring.

“Congratulations, Win. I am so happy for you.”

I was even happier for Rex, her fiancé. He’d get to smell her hair on their pillow every night for the rest of his life.

“I always knew he was right, even at that Trinity frat party when I first met him,” Winnie said as she spooned fresh pesto into a blue enamel pasta bowl. She didn’t say what I knew mattered most: Rex loved her, but not with that “my-life-is-nothing-without-you” desperation that drove her crazy. A parade of high school boyfriends had gotten velcroed to her in exactly the same way I had as a kid. They always ended up needing her too much. I’d watched her peel them off one by one, like bubble gum stuck to her shoe.

I looked around their small apartment, filled with Winnie’s Ralph Lauren fabrics and Rex’s dark leather furniture. Winnie was supposed to live with me, our reunion following four years at different colleges, my chance to prove I’d become sober and responsible and likable again, right? Then at the beginning of last summer, while she waited for me to move to New York, she stayed in this apartment with Rex. Just for a few weeks, she’d said.

Audrey, the roommate I eventually found in Chelsea, was great. But here’s what I wanted to ask Winnie tonight: couldn’t she postpone marriage for a few years, so that we could be roommates, to give me a chance to catch up? If I weren’t right for her as a roommate, how on earth was I going to meet a man right for me? A man like Rex who might ask me to stay for a few weeks and then ask me to stay forever.

Instead I said, “Wow, the ring is beautiful.” It was.

We sat down to eat and she gave me the blow-by-blow on how Rex proposed on the beach during their New Year’s trip to St. Barts.

As we stood side by side in her miniscule kitchen afterwards washing the dishes in hot, soapy water that smelled like lemons, Winnie asked how my love life was.

“Kind of anti-climactic compared to yours,” I said. “All that matters to men here is how much money they make and where they live.”

“Trust me, every guy who walks into the Polo Mansion tells me within 30 seconds about his address and income bracket. Please.” She shook her head and laughed, crinkling the snub nose that was the envy of every girl in high school, including me. I reached into the soapy water and grabbed a bunch of silverware.

“I meet them all over the place, Win. At parties and clubs, of course. Just last week I met a guy on the bus. Someone asked me out while I was standing in line for the bathroom at Isabella’s. Another guy tried to pick me up while I was jogging around the Reservoir. They’re everywhere.”

She handed me a pot to dry.

“For the first time in my life, I have this rule – one of the things I learned when I stopped drinking…” My voice cracked. I bet my face looked like a tomato. I kept talking.

“… is that I will never date a man to satisfy some need of mine or someone who wants me to fill a desperate need of his.”

The words sounded like cheap cardboard. But Winnie nodded, her brown eyes big and reassuring.

“I don’t have sex with them, Win. We don’t even kiss. We talk. For hours. In restaurants I could never afford on my salary.”

She laughed.

“You know, it sounds so innocent, Les. And really fun. It’s just what you need right now, right?”

She flicked soap at my face and a few suds landed on my nose.

Yep, just what I needed. But not what I wanted.

After another congratulatory hug, I headed out into the cold rainy night, exchanging Winnie’s warm, bright apartment for the manicured Upper East Side streets. The heavy brownstone doors of the million-dollar co-op buildings, locked and festooned with polished brass knockers, seemed to declare that everyone in New York was safe at home.

Except for me.

(Crazy Love is a personal history. The events described in this book are real. Many names, except for my own, as well as several geographic and identifying details, have been changed for the usual reasons of privacy and security. A few important characters have been omitted and combined; the character of Winnie represents an amalgam of important friends.)

CRAZY LOVE. Copyright 2008 by Leslie Morgan Steiner. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

A Memoir Of Domestic Violence And ‘Crazy Love’

Former Washington Post executive Leslie Morgan Steiner is a best-selling author with degrees from two Ivy League schools, three adorable children and a loving and successful husband. If you met her on the street you might never guess her secret: that she was once married to a man who beat her with abandon on a regular basis — an experience she recounts in the memoir Crazy Love.

Steiner says when she first met her ex-husband, whom she calls “Conor,” on the New York City subway, she had no inkling that he was capable of such abuse.

“He was really clean-cut, dressed in a business suit,” she tells Michele Norris.

But early in the relationship, there were certain warning signals that indicated Conor’s violent nature. For instance, he referred to her as “retard,” which, Stainer says, was “a term of endearment, as sad as that sounds.”

Then, five days before their wedding, Steiner was working at her home office and couldn’t get the computer to work. Conor burst into the office and put his hands around her neck and shoved her against the wall repeatedly.

“I should have left then, I suppose, but I think that the power of love just overwhelmed my intelligence and logic and rationality,” says Steiner.

Eventually, after years of emotional and physical abuse, Steiner did leave Conor. She moved on to marry a loving man, with whom she has three children. But she still keeps a small box of mementos from her first marriage in her basement — including the last note that Conor ever wrote her, which reads “Goodbye Retard.”

“In some ways, keeping those mementos is a reminder of how far I’ve come,” says Steiner.

Commentary: Rihanna may not be alone

Editor’s note: Leslie Morgan Steiner is the author of “Crazy Love,” a new memoir about domestic violence, and the anthology “Mommy Wars,” which explores the polarization between stay-at-home and career moms.

CNN) — For two days, news reports called her “the 20-year old victim” allegedly attacked by R&B singer and dancer Chris Brown in his car early February 8 in Los Angeles, California.

We all now have good reason to believe that the alleged victim was pop singer Rihanna, Brown’s girlfriend.

The story has dominated the general media with good reason. Both singers are young, apple-cheek gorgeous, immensely talented and squeaky clean — the last couple you’d imagine as domestic violence headliners.

Perhaps the only good that will come from the Rihanna/Brown publicity is destruction of our culture’s misconception that abusers and their victims can only be universally poor, uneducated and powerless.

Brown, whose first song debuted at No. 1 and whose first album topped the Billboard Hot 100, appeared on a Disney sitcom and in Sesame Street, Got Milk? and Wrigley’s Doublemint Gum commercials. Barbados-born Rihanna has been big-brothered by music industry legends like Jay-Z and Kanye West and is signed to the Def Jam Recordings label.

She has been astonishingly successful in the short time she has been on the music scene, attaining five Billboard Hot 100 No. 1’s with “SOS,” “Umbrella,” “Take a Bow,” “Disturbia” and T.I.’s “Live Your Life.”

Like Rihanna, I had a bright future in my early 20s. I met my abusive lover at 22. I’d just graduated from Harvard and had a job at Seventeen Magazine in New York.

My husband worked on Wall Street and was an Ivy League graduate as well. In our world, we were the last couple you’d imagine enmeshed in domestic violence.

Many of my ex-husband’s attacks also took place in our car. For reasons I never understood, the enclosed, soundproof space brought out his worst violence. He punched me so fiercely that my face had bruises from his fist on one side and from hitting the window on the other.

As trapped in the car as I was in our marriage, it was there that I endured tirades about how controlling I was with money, how flirtatious and naïve I was with other men, how defiant and disrespectful I was of my husband’s authority.

So, I suppose I have more understanding than most about the shame, fury, confusion and disappointment Rihanna may be experiencing. What’s hardest for outsiders to fathom is how lethal a cocktail love, hope and sympathy can be. I first fell for my husband the night he confided how he, like Chris Brown, had been traumatized as a young boy by domestic violence in his home.

“He used to hit my mom … He made me terrified all the time, terrified like I had to pee on myself,” Brown said during a 2007 interview with Giant magazine.

Brown hasn’t explained what happened in the recent incident, but this week he released a statement saying that he’s sorry and saddened by it.

Our culture encourages women to nurture men, making it predictable that many experience a seductive empathy for abusive men, as well as the misguided hope that love can obliterate an ugly past.

In my case, it took four years, myriad terrifying attacks, and the intervention of the police and family court before I understood how little I could help my ex get over his abusive childhood.

I certainly felt alone during my abusive relationship, but unfortunately I was in good company. The U.S. Department of Justice estimates that between 1 million and 3 million women in America are physically abused by their husband or boyfriend each year.

Every day, on average, three women are murdered by their husbands or boyfriends. At some point in our lives, 25 percent of American women will report being physically abused or raped by intimate partners, according to the National Violence Against Women Survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

However, these statistics, grim as they are, fail to highlight the root of the abuse cycle. A national survey showed that 50 percent of men who frequently assault their wives also frequently abuse their children.

Witnessing abuse, as Chris Brown and my ex-husband did as young boys, is a form of abuse itself. Tragically, many victims of childhood abuse grow up to be abusers themselves. I always sensed that my husband didn’t want to be hurting me — he knew exactly how excruciating love and fear felt mixed together — but his childhood rage overpowered his adult sensibilities.

A few months after I left my marriage, I happened across another couple in another car, late at night on an empty street. I slowed down as a well-dressed woman about 25 years old was walking away from a white Honda, brushing off a tall, handsome young man wearing a sports coat and jeans.

Suddenly she turned and tried to run. He grabbed her with his long arms and shoved her up against a dirty storefront. Even from my car I could see the fear on her pretty face.

Without thinking, I jerked my car over and got out. By this time the man had let the woman go and she’d slid behind the wheel of the car. He stepped back as I approached, his anger displaced by uncertainty and shame at being interrupted. I didn’t look at him. I leaned into the car as she sat clutching the wheel, crying and staring straight ahead.

“I just left a husband who beat me for three years,” I said. “You do not have to put up with this. You do not deserve to be treated like this.”

“I know,” she whispered as fresh tears poured down her face. She sniffed loudly and shook her head. She wouldn’t look at me. Her eyes were rimmed red, but I could see resolve in them.

“You’re right,” she said. “It’s just taking me longer than I thought.”

As I left, I gave the man a long stare. The spell had been broken and his face was open, sorrowful, filled with hope and fear — a look I had seen dozens of times on my husband’s face. How long would that look last before he got angry again? I could feel the woman’s determination as I got back into my car. I knew she would be all right, one day. The man, I was less certain about.

Family violence is a criminal act; perpetrators, while often former victims themselves, need to accept culpability. Until we can prevent children from witnessing and becoming victims of abuse, the cycle will repeat itself: there will be many more Chris Browns and “alleged victims” in our headlines and in our homes.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Leslie Morgan Steiner.

Crazy Love

Deborah A. Kelly writes: Crazy Love, a memoir by Leslie Morgan Steiner, is a stark reminder that domestic violence is not the exclusive purview of the poor or of immigrant cultures. Steiner reminds us that violence within romantic relationships can happen to anyone and anywhere, even trust-fund Harvard grads with promising careers. The physical and emotionally abusive love that Steiner shares with her readers is astounding in its simplicity and complexity. It is simple because the violence is clear and brutal: silver photo frame smashed over her head, clenched fists punched into face, cold gun held to her head. Complex because the emotional manipulation perpetrated by her husband is subtle and crafty. He isolated her from friends, made her quit her job, moved her to another state, nicknamed her Retard. Under the guise of conducting research, Steiner tracked down an assistant professor pursing a Ph.D. on the behavioral psychology of batterers. Primed with interview questions, Steiner learned: 1) of primary importance is that the batterer accept responsibility for his actions, and 2) even upon those rare cases of acceptance, most batterers keep on battering those they love. “Men I work with,” said the assistant professor, “cannot separate intimacy from abuse.”

During a visit to a marriage counselor, Steiner’s husband told her to stop pushing his buttons. He said that the purpose of the counseling was to improve their communication, and handed Steiner a list of conversational subject matters she must avoid. Steiner, confused, thought they were seeking counseling so he would stop hitting her. It occurred to her that this was not a man who was accepting responsibility, rather one that still believed she was to blame for his violence. Later, Steiner opted for a restraining order and a divorce. Steiner recounts, “I will probably always flinch when a man, any man, raises his voice, whether it’s in a boardroom or my backyard.” The high price she paid for marrying an abusive man is less than most pay. She recognizes that by proclaiming profound luck to have, while in her twenties, learned to recognize, and stay away from, abusive men. Others should be so lucky.

Author Tells Her Story Of ‘Crazy Love’ And Abuse

Leslie Morgan Steiner seemed to have the world at her disposal. She was in her 20s, a Harvard grad with big ambitions, living and working in New York City.

Until she met Conor.

“He was so intensely interested in me,” says Steiner of meeting the man who would later become her abusive husband.

The two dated for some time and later moved to New England, where they made plans to marry. But not before Steiner became harshly acquainted with Conor’s violent streak.

A Broken Computer

“The first physical attack started five days before our wedding,” she recalls.

Steiner said she was working on a broken computer when she expressed frustration. That didn’t sit too well with Conor.

“His rage just took over. He grabbed me around the neck and he squeezed my throat … and he banged me against the wall several times and then kind of threw me down on the floor, and then left,” she describes.

Although Steiner did attempt to seek help after that first attack, she didn’t believe it was enough to justify calling off the wedding.

“I never knew anything about domestic violence … I [just] thought I was in love with a very troubled man,” she says.

But things did not turn around. In fact, the situation grew worse. Steiner says being beaten twice on her honeymoon was only the beginning of a marriage mired in abuse and isolation from her family and friends.

“He worshipped me and denigrated me at the same time,” she explains.

After years of absorbing the physical and mental trauma, Steiner finally had all she could take.

The Final Beating

After spending a summer apart from her husband, Steiner resolved that she could no longer take the abuse. She told her husband not to hit her again and had an epiphany of sorts.

“It was like a stranger was in my bedroom, choking me and kicking me,” she says.

But she realized the severity of her situation when Conor beat her for what became the last time.

“That final beating, it changed something in me. It made me realize this was a very dangerous game I was playing,” she says. “All of my denial dissolved.”

Steiner is now happily remarried and has a new family. Looking back, she understands that things could have ended another way.

“I’m very lucky that I’m alive.”

Steiner tells her story in the new book, Crazy Love.

Book of the week: Crazy Love by Leslie Morgan Steiner

The 10 small bruises on Leslie Morgan Steiner’s neck were hardly visible on the day she got married. Her new husband, “Conor,” had left them there five days earlier, when he grabbed her by the throat and held her against a wall because she had uttered a complaint about their new computer. Steiner was a writer for Seventeen magazine. She knew the right thing to do was to call a domestic abuse hotline. But when she drew a busy signal on the first try, she didn’t follow through. Nor did she rescue herself at any time over the next three years, when Conor punched her in the face, threw her down a set of stairs, or put a gun to her head. In fact, Conor walked out on her first.

Steiner’s “compulsively readable” account of her nightmare first marriage dares readers to ask: Why didn’t she leave? said Kim Hubbard in People.The young Harvard graduate didn’t fit the stereotype of a trapped spouse. Raised in privilege, she had the means to support herself, and the couple had no children to worry about. Crazy Love suggests that it’s easy to understand why women in her position find it difficult to walk away, but that’s wrong, said Linda Hirshman in Slate.com. Steiner’s mention of being “kind, insecure, and desperate for intimacy” isn’t enough. Democracy is built on a communal assumption that individuals, no matter how “kind” they are, “can be trusted to look after themselves.” Our tendency to absolve spousal-abuse victims of any responsibility for their plight smacks of “the soft bigotry of low feminism.”

That’s cold, said Katha Pollitt in The Nation. We know a lot about why battered women stay with their husbands. Conor and men like him “are good at isolating their partners from friends, family, and other sources of support and help.” Read Crazy Love carefully, and you’ll notice that it makes “painfully clear” an additional dynamic that hasn’t often been written about. We see Steiner failing to break away from her batterer “because she pities him and wants to rescue him from his demons.” Women are like that; they see themselves as caregivers. The ones who are in trouble don’t need “moralistic lectures masquerading as feminism.” As Steiner points out, they need people around them to be courageous enough to help.

Why Love Can Turn Violent

Leslie Morgan Steiner would seem to have it all worked out. She has degrees from Ivy League schools, a long stint under her belt as a columnist for the Washington Post and a bestselling anthology, Mommy Wars, which took on the feminine work— life balance myth by embracing the fact that most women’s jobs and lives will never be perfect. But her successful present belies a haunting past: In her new memoir, Crazy Love, Steiner reveals how she fell in love with and married a man who beat her regularly and nearly killed her. TIME spoke to Steiner about why she decided to write about the most painful period in her life, what lessons she hopes readers can draw from her experience and why she thinks people should defend Chris Brown.

Why did you choose to reveal your secret now? Similar to Mommy Wars, this memoir allowed me to dig deeply into a very personal issue. It allowed me to answer a series of why’s and find out things for myself. Honestly, I really wanted to understand why I had been vulnerable to a man like my first husband and why I had ignored so many red flags. It’s an incredible thing to take something bad that happened to you and turn it into something good. Writing Crazy Lovewas that for me.

You mentioned that sharing this story is either one of the stupidest or bravest things you’ve ever done. Which is it? And why the vacillation? Well, Both. Stupid because of how vulnerable sharing this story makes me feel. Stupid because I worked so hard to put this behind me. Stupid because it is painful and upsetting to talk about this period in my life. Why bring such a dark period into my wonderful, happy present day life? And brave because it is hard and painful for anyone to talk honestly about a terrible relationship.

How does this memoir complement, if at all, a discussion on working mothers? It’s all about balance. And the hallmark of both Mommy Wars and Crazy Love is candor. You have to push yourself to be very honest. Even about things you don’t like about yourself. In a nutshell, the reason I wrote Mommy Wars is because I got so tired of women saying, “My life is so perfect. Everything is perfect” when no — it actually is not. Candor is so valuable. With domestic violence, candor is the total answer; it is a syndrome that is made worse by its bedrock — secrecy.

Many females insist that the buck would stop for them after their first brush with any type of abuse. How do you handle the consistent parade of questions on why you stayed? It’s nothing I can explain in a sentence. Instead of asking “Why did she stay,” the far more troubling question is “Why on earth would a man abuse the person who loves him the most?” What amazes me is that almost every person whom I talk to asks me a question that turns my stomach: “how does your ex-husband feel about your writing this book?” And I will tell you, if I had been raped twenty years ago by a stranger and decided that in order to heal, I had to write about it, no one would ask me why I had come forward. A lot of people told me to publish Crazy Love anonymously. If I did, I would be saying I am ashamed. Society promulgates the notion that victims should feel damaged. I tried to ignore the voice in my head telling me that I was.

For years, you wrote and edited for Seventeen magazine. How has your relationship to young women shaped this memoir? Being a teenage girl is one of the most profound times in a female’s life. And I think in some ways it is a more transformational time than male puberty. That’s why I love the Twilight series. It’s all about a girl discovering her immense power of a being a woman. I have always been fascinated by the issues that women grapple with. And I think it’s a very interesting time to be a woman, especially in this country. Our roles are changing so rapidly.

You spend a good portion of time talking about that transformational time in your life — your battles with anorexia and substance addictions. How much of your relationship with your ex-husband do you attribute to your teenage years? A lot, but I think the answer is more complicated. The easy, pop-psychology answer would be to chalk my abuse up to self-esteem issues. But because at an early age I had overcome anorexia and faced head-on a tendency toward addiction, I was overly confident. I had gone to Harvard, I had solved all these really big problems. I wasn’t out to solve world hunger, but I thought I could take on the problems in my own universe. I was blind to my own vulnerabilities — blind to the fact that I was human.

Much like the discourse surrounding The Mommy Wars there is a lot of finger pointing at women when it comes to domestic violence. What do you make of this seductive empathy for abusive men?The bottom line is simple. No one ever has the right to hit you. Nobody. What gets murky is that our culture is filled with the mythology that women are taught to nurture men, accommodate their weaknesses, and overlook their failures — that women are much more intuitive emotionally, so they should help men unearth their childhood traumas. I think a lot of that is why I get sucked into this savior fantasy. I thought it was my role as a woman to help my ex-husband. Women think they can take on anything and that we’re supposed to. We live in a patriarchical society that puts women in a lot of impossible situations.

It’s timely that Crazy Love is released right after Chris Brown and Rihanna’s relationship has seized the public’s attention. What can we learn from the torrent of headlines? It’s a strange blessing that this story has played out because there needs to be a spotlight shed on domestic violence. They’re giving the country a great education about what domestic violence is really like because neither of them fit many of the stereotypes people hold on domestic violence. I have a lot of sympathy for both Chris Brown and Rihanna and in some ways people are right to defend Chris Brown. He’s not a demon; he’s a troubled man who needs help, but Rihanna should not go back to him. She is the last person who can help him. The only thing you can do to help him is to leave. It is good that our country is so publicly engaged and trying in our own awkward and fumbly way to understand the craziness of it all.

Parenting Kids With An Appetite For Politics

In this week’s parenting segment for moms, Jolene Ivey and Leslie Morgan Steiner weigh the value of engaging children early in the political process. Also, Ivey’s son, Alexander, and Steiner’s son, Max, explain how, as youngsters, they’ve discovered their own political passion.

MICHEL MARTIN, host:

They say it takes a village to raise a child, but maybe you just need a few moms in your corner. We visit with a diverse group of parents every week for their comments and some savvy parenting advice. Today, we want to talk about party training.

This election season has offered great opportunities to get kids involved in the political process. No matter if you’re raising a wee Republican or a Democratic shortie or perhaps even a member of the green party, the seeds of involvement in politics can be planted early. So, how do you encourage your kids to take an interest in politics? Do you even want to? And what do you aim to teach?

I’m joined by Jolene Ivey, co-founder of the Mocha Moms, a parenting support group, and Leslie Morgan Steiner, editor of the “Mommy Wars,” it’s a collection of essays about the real-life dilemmas faced by moms today. I’m also pleased to welcome their sons to the program, Alex Ivey, who’s studying at Columbia University in New York, and Max Steiner, a sixth grader at a local school in the district. Welcome, moms and sons.

Ms. JOLENE IVEY: Hey, Michel.

Mr. MAX STEINER: Hi.

Mr. ALEX IVEY: Thanks for having me.

MARTIN: Now, Jolene, in addition to being one of our regulars, you and your husband are both public officials. Do you think you’ve consciously set out to teach your kids about politics, or you think it’s something that they just picked up by osmosis?

Ms. IVEY: Well, it’s kind of like osmosis, if you would count that as being going to the polls with me ever since you were born.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Ms. IVEY: So, from the very beginning, every time I went to work a poll for a candidate or for a cause, I would bring my kids along, partially because what else am I going to do with them and partially because I thought that it was good for them to participate. So, they would take the handout and hand it to people also, and most people would be really nice. No matter at which side of the aisle or position they were on, they would be happy to take a piece of paper from some cute little boy.

MARTIN: Alex, what do you think about that? Did you love it? Did you hate it?

Mr. ALEX IVEY: I mean, I thought it was great. I always love debates. So when we were talking about, you know, certain political issues around the Thanksgiving table, I thought that was really fun.

MARTIN: Leslie, what about you? Do you think you’ve set out to consciously teach your kids about politics? Or you think it’s just something that they picked up?

Ms. LESLIE MORGAN STEINER: I think I consciously set out to make them be aware of politics. You know, I grew up in Washington D.C. My dad is a Democrat. My mom is a Republican. And one of the best things about growing up here was just having politics in the background all the time. And that’s one reason I moved back here and wanted to raise my kids here, so that they can have it as just an important part of their daily life.

MARTIN: Max, what about you? Your mom tells us you’re very interested. True?

Mr. STEINER: Oh, yeah, I am pretty interested. And the last election, I was in second grade, and I was a little too young to really understand it. But now, I’m 11 years old, and even though I can’t vote and most of my thoughts are based on my mom and dad, I still think that it’s pretty cool and – yeah.

MARTIN: What do you think got you interested? What most interests you? Do you like looking at the commercials? Do you like going to the polls? Do you like talking about stuff with other kids at school?

Mr. STEINER: Well, it’s a lot of fun to talk to my friends about it. Most of them like the candidate that I would like. But it’s also fun because there are a few opposed, and I debate with them sometimes. And that’s a lot of fun, just to do it in a playful way with some of your friends. But it’s also been fun seeing like those commercials about, like, some of the insane things they say, and also, I watch “Saturday Night Live” every once in a while, and seeing those skits, it’s just hilarious.

MARTIN: Jolene, what about what Alex – I mean, I’m sorry, Max was talking about some of the insane things that people say. Do you ever worry about your kids being exposed to some of the uglier things that people talk about in politics?

Ms. IVEY: I’ll tell you. We were working a poll one time on behalf of an issue that was extremely contentious in our area. And the position that we advocated for, some of the people who came to the poll who were on the other side, instead of being willing to, as I said before, be happy to take a piece of paper from a cute little boy, they were kind of nasty.

And that really annoyed me because I feel like any reasonable adult should be able to take a piece of paper from a kid, even if all you’re going to do is throw it in the trash and vote the other way. That’s fine. But I think that that particular time is the only time, as far as civic involvement, that there’s been a real ugly thing. As long as you can talk about it, you can get through anything.

MARTIN: Alex, do you remember that? How do you feel about that?