Infertile Americans Go to India for Gestational Surrogates

Rhonda and Gerry Wile of Mesa, Ariz., struggled with infertility for years. At first, Rhonda failed to get pregnant because her husband had not told her about a vasectomy he’d had in his first marriage. The news, received by an email in 2004 when he was serving in the Coast Guard in Kuwait, nearly derailed their four-year marriage.

Gerry had his vasectomy successfully reversed, but after suffering a miscarriage, Rhonda was diagnosed with uterus didelphys, a not too uncommon condition with a septum or dividing wall between two vaginas that leads to a double uterus. They said she likely could not sustain a pregnancy full-term.

So the couple turned to gestational surrogacy, a growing trend among American women for whom in vitro fertilization is not an option. They didn’t stay in the United States, but went abroad to India, where surrogacy is now one of the fastest-growing segments of the medical tourism business.

Having two vaginas is not so rare.

“When doctors told us surrogacy was one of the options for us and then a young lady at work told me the price, I felt we had hit a roadblock again,” Rhonda, a 43-year-old nurse, told ABCNews.com.

But today, the Wiles have three children, a 4-year-old boy Blaze, and 2-year-old girl/boy twins, Dylan and Jett. Gerry, a 47-year-old firefighter, made one sperm donation in April 2008, and their children were conceived though a Muslim Indian egg donor the couple had never met. All three are full biological siblings.

“We knew it was huge to go to India,” said Rhonda. “We could show up and it could be a phony website and we could be taken for a ride. But as we got more familiar and deeper into the process, our fears faded away. We met the doctors and spent time with them and there was an immediate connection and sense of trust.”

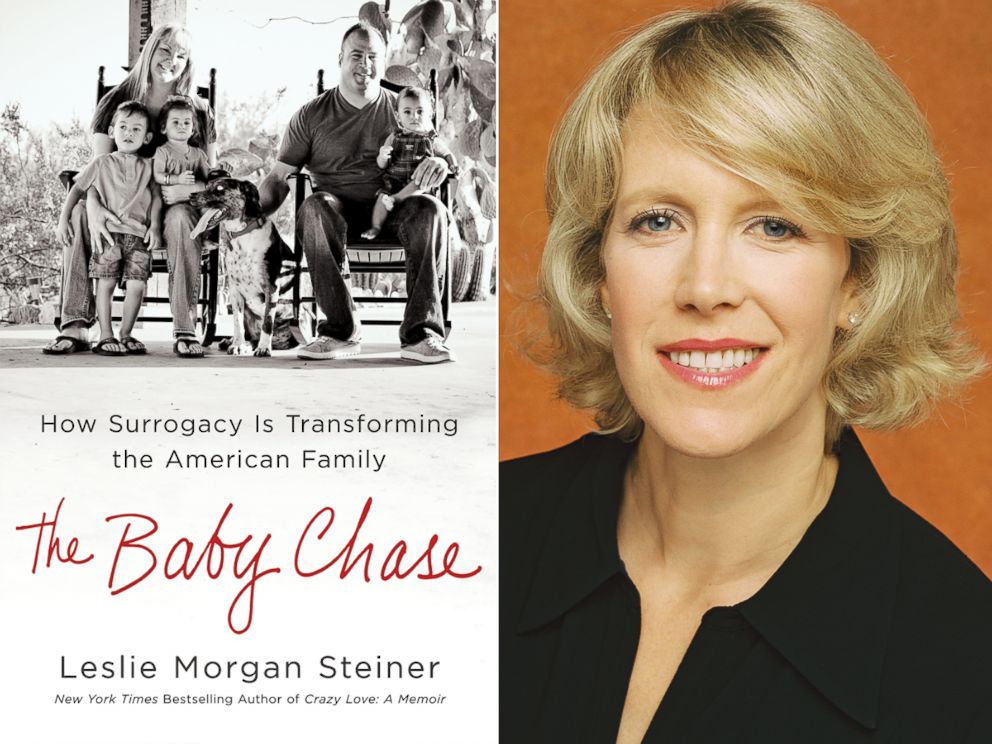

Their unusual but touching journey is the subject of Leslie Morgan Steiner’s new book, “The Baby Chase: How Surrogacy Is Transforming the American Family.”

“I wanted to look at what happens when we can’t have children and the lengths we go to,” said Steiner, author of “The Mommy Wars” and “Crazy Love.” “How far would I go to have a baby? As I got into it and learned more about it, I realized there were complex medical, ethical and religious issues. It was so multi-faceted.”

“Infertility is a cruel and crippling disease, and surrogacy is one of the solutions — for some, it is the only solution. — Leslie Morgan Steiner”

Steiner followed the Wiles to India to investigate the private clinic where their children were conceived and to meet the gestational carrier of their twins.

The cost for all three children was about $50,000 compared to an estimated $100,000 a child in the United States. And the Indian women who carried the pregnancies, who typically earn about $60 a month, each received the equivalent of $6,000.

Indiana couple braces for second set of triplets.

What India has to offer, according to Steiner, is “world-class private hospitals, an abundance of English-speaking doctors, and a plethora of poor, but healthy women of childbearing ages.”

No data yet exists on how many surrogate births take place in India, but Steiner contends India has become the largest provider to infertile couples in the Western world outside the United States.

These are reputable clinics, according to Steiner. “They only want mentally and physically healthy surrogates who have already had children and have proven their fertility and can gestate a baby and women who understand the complexity of what they are doing.”

“When you have a baby 8,000 miles away, you need a lot of reassurances that the surrogate is going to get good medical care,” she said. “They sign a contract not to have sex, to take vitamins and eat healthily. The clinic goes the extra mile to cook and take care of them and they see the doctor in a regular basis.”

Legal since 2002, gestational surrogacy is thriving in more than 1,000 clinics in India. According to a World Bank report, the commercial surrogacy industry in that country will reach $2.5 billion by 2020.

A bill is before the Indian Parliament that will for the first time regulate this nascent industry, but critics say that its provisions lack adequate protections for the women who act as surrogates.

But Steiner argues it is “empowering” for these women. “India is a very sexist and paternalistic country. The vast majority of women never work their entire lives. … But a woman can buy a house or pay for the lifetime education of her children. Going in as a Westerner, you think these women are being taken advantage or exploited, but it’s exactly the opposite. They become heroes in their families and among their neighbors.”

Dr. Sudhir Ajja, co-founder of Surrogacy India, the Mumbai clinic where the Wiles’ children were conceived and delivered, said about 95 percent of his clients are international — 30 to 40 percent Americans, followed by Australians and Swedes. His clinic, founded in 2007, delivers about 302 babies a year, averaging 15 to 20 new pregnancies a month.

He and his co-founder had seen clinics doing surrogacy on an out-patient basis and said they wanted a more “humane” approach with more medical oversight.

Surrogate mothers are put through a rigorous screening process for physical and psychological health, and the clinic rejects more than a third of them.

At first, surrogacy was considered shameful by Indian women.

“Things have changed,” Ajja told ABCNews.com. “We have thousands [of women offering to be surrogates]. We now get referrals from sisters, sisters-in-law and word of mouth.”

The surrogates receive free medical care, food and even housing close to the clinic, where they can be monitored by medical professionals in the third trimester. The fee paid by couples includes the surrogacy fees, IVF, medical testing, legal documents and passport assistance.

Author Steiner doesn’t suggest there are no potential problems with international surrogacy. “It’s not a perfect world,” she said. “India has a big problem with forced prostitution and there is a high incidence of female infanticide. So it is a bit ironic that surrogacy is flourishing.”

Rhonda learned about the Indian clinic on an “Oprah” show and then by searching the Internet. When they saw the cost, about $26,000, she said, “I thought it was do-able.”

The only references the couple had was a man from Spain, “who spoke very broken English,” said Rhonda. But when they arrived in India and saw the birthing hospital and the accommodations for the surrogates, “we felt good about the process,” said Rhonda. “It was very professional.”

Through both pregnancies, the Wiles kept in touch with the surrogates via a language interpreter on Skype. When Blaze was about 18 weeks in utero, the couple decided to go to India and meet his surrogate.

“We wanted to see the ultrasound and we set up a meeting and made the trip to go halfway around the world,” said Rhonda. “It was fabulous.”

What she learned was that the woman was the mother of two boys, married to a factory worker. “She did basically what 90 percent of the surrogates do – she wanted to buy a house as her goal.”

As for the twins, their surrogate “was poverty-stricken,” said Rhonda. “She needed money to survive and was having a hard time making ends meet. Her husband was out of work quite often and she needed to put food on the table.”

Now, on her blog, Our Journey to Surrogacy In India, Rhonda recommends her experience to other infertile American couples.

“We became a reference for others,” she said. “It’s amazing. People have sent me messages and still thank me for their children: ‘Without you, we would not have a child.'”

As for Steiner’s book, Rhonda said, “I loved it. I read through the entire book and took time to read it quietly and in detail to bring it all in. I literally relived my whole journey through her eyes. I cried. I laughed. I lived it through her.”